Perspectives on the Atonement: seeking an agreed way forward

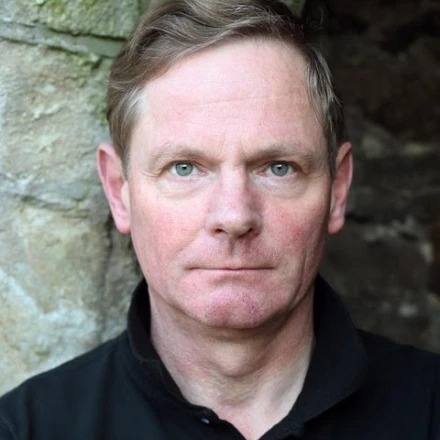

KNOWLEDGE is furthered by disagreement; but how that disagreement is expressed is crucial. Both ordained for the province of Armagh in 2012, but with contrasting perspectives, two Church of Ireland clerics engage with one another below on one of the most hotly debated topics in the Church today: that regarding nonviolent and cross- centered theories of atonement. Andrew Campbell: WHEN we look across the spectrum of western theological discourse over the early years of this century we see that the nature of atonement is a dominant subject for debate. Behind much of this debate is rejection of violence (namely the cross) as a means by which atonement is won. Over the last years of the 20th century and the early 21st century thinkers such as Rebecca Ann Parker, Rita Brock, Rosemary Radford Ruether and J. Denney Weaver have highlighted their problems with cross-centred atonement theologies. (By ‘cross-centred’ I refer to any view of the atonement in which the death of Christ is divinely ordained.) These nonviolent theorists reject the idea that atonement was achieved through a violent act perpetrated against Christ, leading to the now infamous claim that “divine child-abuse is paraded as salvific.”1 This has given rise to nonviolent atonement theologies that deny that the death of Christ was divinely ordained.